Out

of the Ring

and Into the Den

Very few Kennel Club

terriers actually hunt. Here's why.

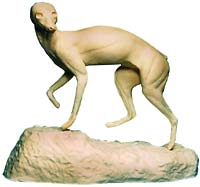

Red Fox

Wasco Taxidermy Mount Manikin, 14 inch chest

"Was she the runt of the

litter?"

I look up to see a slightly overweight woman walking her

dog around the edge of a grassy parking area.

"No, ma'am. She's a hunting Jack Russell -- they're

bred this size to do earth work."

"Oh yes," she sniffed, "groundhog holes

are so small. Noodle's wasn't bred for that - her type

were bred to go after red fox."

I look down the leash. There sits a solid dog with

thick legs, a cinder-block head, and a chest bigger than

a mailbox, a very happy look on its face.

"Yes ma'am," I reply. "That's what they

say. Noodles sure looks like a happy dog. How old is

she?"

A

working dog should fit inside a

mailbox, not have a chest as big as one.

Some variation of this conversation invariably takes

place when I go to an AKC go-to-ground trial with my two

terriers - a small female Jack Russell and a large male

Border Terrier.

At one time or another in these conversations, I have

been told that hunting terriers need long legs to

"follow the horses" and that "short legs

are needed for a dog to be able to go to

ground." I have been told that certain breeds

have huge heads and jaws "in order to kill

badgers," and that dramatically elongated heads

"set the eyes far enough back that they can't be

bitten by a fox." I have been told that

"colored dogs will get ripped up by fox

hounds," and that the solid coated Border terrier is

"the last true hunting terrier." And

again and again I have been told that, "the British

fox is much larger than the ones we have here in

America".

I listen, but I don't believe much of it anymore.

In truth, very few terrier owners hunt their dogs, and

most terrier owners have never seen a fox much less a fox

den. In this increasingly urban world it is a lucky

accident if the average terrier manages to nail a rat,

field mouse or mole. Such accidental take is not the

specialized work that terriers were bred to do,

however. As Captain Jocelyn Lucas notes in Hunt

and Working Terriers (1931): "Working

terriers means, in sporting parlance, a terrier that will

go to ground on fox, badger, or otter, and not merely a

dog that will kill rats or hunt out

rabbits."

Badger and otter hunting with terriers has been illegal

in England for nearly 30 years, however, and it looks

like fox hunting will soon follow. If Jocelyn Lucas

were alive today, he would be standing in a visa line

waiting to come to the U.S., where red fox, gray fox,

groundhog, possum and raccoon are in abundance and where

badger and nutria can also be worked in some

states.

If you want to hunt in America, all you need is a proper

dog.

A Proper Dog

A "proper dog," of course, is harder to get

than it sounds.

For one thing, almost all the dogs you see at Kennel Club

shows are too big to actually work. In fact, this

appears to be true in Great Britain as well where most

hunt terriers are small ununregistered Jack Russells,

patterdale-type fell terriers, crosses, or dogs of

“pedigree unknown.” The naturally small

Kennel Club breeds that do exist rarely see hunt service

as they are likely to have other failings as far as the

hunter is concerned -- lack of gameness, lack of nose,

lack of voice, or lack of judgment, to name just four

common faults.

While nose, voice, gameness and judgment are all

important attributes of a working terrier, no attribute

is more critical than size.

If a dog cannot get down a hole, nothing else matters.

Perversely, however, while size is the one characteristic

of a hunting terrier that is easily measurable in the

show ring, it is also the one attribute of a working

terrier that is most shrouded in misrepresentation and

ambiguity.

Consider the Border Terrier, for example: the

American Kennel Club standard for the breed says

"the body should be capable of being spanned by a

man's hands behind the shoulders."

This is a ridiculously imprecise measurement. Which man's

hands? Does this mean there can be no women

judges? And if the average man can span a 19-inch

dog, does this mean such a dog is actually capable of

going to ground in a natural earth? Finally, if the

standard for the Border Terrier is supposed to reflect

the requirements of a working dog, why is the entire

shoulder and chest area of the Border Terrier – a

clear determinant of whether a dog can actually go to

ground -- afforded only 10 points out of a possible

100?

Walter Gardner, in his book, About the Border Terrier,

notes that “the earlier border, which was bred for

work rather than exhibition, was certainly smaller than

many borders we see today,” and describes Jacob

Robson’s Flint, one of the most famous working

border terriers, as weighing just 12 pounds.

The typically show-ring border terrier we see today

weighs half again as much and has a chest span of about

17 inches.

The fact that chest span is given such short shrift in

the show ring is hardly surprising when one considers

that many people think a dog has proven its worth if it

can merely shove its head and shoulders into a den

entrance.

In fact, a true working dog should be able to enter a fox

den or groundhog sette and negotiate the entire pipe

– from main entrance to bolt hole -- without having

to be dug out of the ground. In a natural earth

this den pipe will be 15 to 40 feet long and will rise

and fall, twist and contract, challenging the dog at

every turn.

A dog that routinely fails this challenge is not a useful

dog. In fact, hunting with a large dog that cannot

get past the first turn is nearly impossible, as it

requires a team of diggers to sink a new hole whenever

the tunnel changes direction, and in the end you may end

up excavating the entire length of the den.

A large dog in a small hole is also a danger to

himself. A terrier that has to dig hard in order to

move up a tunnel is a dog that has to push dirt behind it

in order to make progress. As earth is shoved to

the rear, a dirt wall can easily form just behind the

dog, "bottling" it off from its air

supply. Because a digging dog is working hard and

breathing hard (as is the quarry) asphyxiation

underground is a very real possibility.

A small dog, on the other hand, can simply scoot over

small dirt mounds and around constrictions and

obstacles. Not only will such a dog face the quarry

with more energy and more air, it will also have room to

maneuver to avoid a bite and force a bolt. A larger

dog, on the other hand, may find itself face to face with

the quarry, jammed tight in the pipe, already tired, and

with a dwindling air supply. Only tragedy can come

out of such a situation.

A Fox is Not a Coyote

Ken James, who hunts his Wills View pack of Jack Russell

terriers in the mountains and farm country of Western

Pennsylvania, has measured the chest size of a wide range

of terrier quarry. His conclusion is that any dog

with a chest larger than 14 inches around is going to

have a very difficult time.

Quarry

Average Chest Size

Smallest Chest Size

Number Measured

Groundhog 14 inches

12 inches

65

Red Fox

13 inches

11.5 inches

6

Gray Fox

12.5 inches

10.5 inches

10

Raccoon

14.5 inches

11 inches

30

Measurement from Ken James' book:

Working Jack Russell Terriers in North America: A Hunter's Story

What is fascinating about these measurements is how

clearly they demonstrate a simple fact: the chest

size of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is almost exactly the

same as that of the North American groundhog or woodchuck

(Marmota monax).

Many Kennel Club terrier owners find this hard to

believe, and some argue that the fox dens they have seen

have larger entrances than the average groundhog

sette.

This last point is true, but only for the first three or

four feet of a red fox den. Here, at the front

entrance, the fox excavates the groundhog hole into a

vertical oval so that it can bolt out of the den at a

trot. Farther back from this first three or four

feet of excavation, however, a groundhog sette is

generally left as it was found, with a fox able to exit

the same carefully disguised bolt hole the groundhog once

provided for himself.

Gray

Fox

Wasco Taxidermy Mount Manikin, 14 inch chest

When confronted with measurements of American red fox

chests, some American terrier owners will argue that the

North American red fox is a different species than its

European counterpart and therefore must have a smaller

den.

This is simply not so.

The red fox is an import, brought to the United States in

the 1600s because the native gray fox would climb trees

when chased by men on horses. British redcoats,

anxious to continue their fox hunting tradition in the

New World, brought with them the quarry they required for

their sport, and the red fox flourished as forests fell

to fields. Not only are there more red fox in

America today than at any other point in history, there

are also more groundhogs, more gray fox, more raccoon and

more possums – all due to changing habitat which

worked to encourage more of these agricultural

opportunists.

In both England and the United States the size of the red

fox is quite variable, with larger animals generally

found in the north, and smaller animals in the

south. In The Working Terrier British

terrierman D. Brian Plummer notes that he has caught fox

as small as 6 pounds and as large as 20 pounds but that

"the average weight for adult fox is roughly 14

pounds, and vixens are usually smaller than

dogs."

In his book, How to Spot a Fox, J. David Henry

notes that the average adult red fox in the U.S. ranges

from 5.5 to 12 pounds in southern states and between 11

and 20 pounds in northern states. Henry reports

that in Great Britain the red fox ranges from 11 to 16.5

pounds for dogs and from 10 to 14.5 pounds for

vixens.

In short, the British and American red fox are exactly

the same creature and they are exactly the same size,

with foxes on both continents having a mean size of 10 to

14 pounds.

It should be said that a 12-pound fox is not built like a

14-pound dog, but like a 12-pound tabby, with a tiny

chest, and bones that seem almost elastic. Fox

biologist J. David Henry, in fact has entitled one of his

books, Red Fox: The Catlike Canid in order to

stress both the morphological similarity of the cat and

the fox, and their nearly parallel hunting styles.

A 14-pound dog will find it difficult to follow a 10 or

12-pound fox to ground in a tight earth because, in all

likelihood, a dog this large will have a chest that is at

least 2 inches too big.

The dog you need in the field has a chest span of under

14 inches and will probably stand little more than 12

inches tall at the shoulder and weigh in at 9 to 12

pounds – a mere shadow of the dogs we typically see

winning in the show ring.

A dog this small can follow a fox to ground and negotiate

the average groundhog den with relative ease – they

are, after all the same-sized sette.

This last fact seems to disappoint some terrier

owners. Perhaps this is due to the anglophile

streak we see among many terrier owners – a

glorification of all things British, with a latent

suggestion that American dogs and American quarry

must somehow be inferior. The royalist image of

wealthy redcoats riding to fox is, after all, more

attractive than that that offered by the American

terrierman slogging through pastures dressed in overalls

with a sharp spade over one shoulder.

That said, the terriers needed by both parties are

exactly the same, and a proper dog for red fox is also a

proper dog for groundhog, gray fox, and raccoon.

The fact that the majority of Kennel Club dogs on both

continents cannot make it in the field has less to do

with changing quarry or changing geography than it does

with show ring standards that cloud the issue of size

while at the same time giving the bulk of all show ring

points to such non-essential characteristics as eye

color, nose color, the lay of the ears and the carriage

of the tail.

The good news is that even as England and Scotland move

to ban fox hunting with dogs, hunting with terriers is

beginning to take hold here in America.

While the best days of the British working terrier may

lay in the past, the best days of the American working

terrier lie immediately ahead. Those that would

prefer to work their dogs in the real world, rather than

fantasize about the nature of working dogs in a far off

land, need only find a small terrier out of working stock

to start their journey.

Raccoon

Wasco Taxidermy Mount Manikin

16 inch chest_____________________________________

FOX DENS OF THE WORLD

This is a picture of a fox den in

Australia made out of an enlarged rabbit hole cut in a

railway embankment. Note the oval shape where the fox has

made the entry deeper to allow it to bolt while standing

up. This oval den expansion will disappear 3 or four feet

into the den entrance.

This is a picture of a fox den in

Australia made out of an enlarged rabbit hole cut in a

railway embankment. Note the oval shape where the fox has

made the entry deeper to allow it to bolt while standing

up. This oval den expansion will disappear 3 or four feet

into the den entrance.

Another fox

den, this one in Europe.

Again, note the oval shape.

Maryland Fox den made from

groundhog hole.

Jack Russell

exiting Virginia fox den. Two fox were bolted from this

den. The picture below this one is the same den, but the

entrance hole.

Jack Russell

exiting Virginia fox den. Two fox were bolted from this

den. The picture below this one is the same den, but the

entrance hole.

.